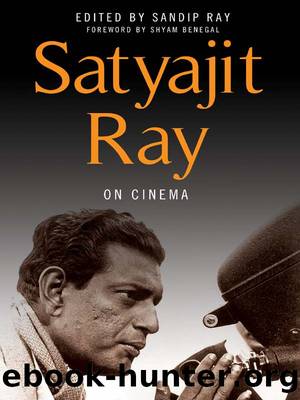

Satyajit Ray on Cinema by Satyajit Ray

Author:Satyajit Ray [Ray, Satyajit]

Language: eng

Format: mobi

Tags: Video/Direction &, ART016020, PER004010, Performing Arts/Film &, Production, Art/Individual Artists/Essays

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Published: 2013-03-04T16:00:00+00:00

Dayamoyee (Sharmila Tagore) as the goddess in Devi

Amal (Soumitra Chatterjee) and Charu (Madhabi Mukherjee) in the garden sequence in Charulata

In a film like Charulata, which has a nineteenth-century, liberal upper-class background, the relationship between the characters, the web of conflicting emotions, the development of the plot and its denouement, all fall into a pattern familiar to the Western viewer. The setting is a Western-style mansion, the décor is Victorian, the dialogue strewn with references to Western literature and politics. But beneath this veneer of familiarity the film is chock-a-block with details to which he has no access. Snatches of song, literary allusions, domestic details, an entire scene where Charu and her beloved Amal talk in alliterations (thereby setting a hopeless task for the subtitler) â all give the film a density missed by the Western viewer in his preoccupation with plot, character, the moral and philosophical aspects of the story, and the apparent meaning of images.

To give an example, early on in the film, Charulata is shown picking out a volume from a bookshelf. As she walks away idly turning its pages, she is heard to sing softly. Only a Bengali will know that she has turned the name of the author â the most popular Bengali novelist of the period â into a musical motif. Later, her brother-in-law Amal makes a dramatic entrance during a storm reciting a well-known line from the same author. There is no way that subtitles can convey this fact of affinity between the two characters, so crucial to what happens later. Charulata has been much admired in the West; so have many of my other films. But this admiration has been based on aspects to which response has been possible; the other aspects being left out of the reckoning.

Even those films of mine which have been admired have often been described by Western critics as being slow. Indeed, they often are slow, and there are several reasons for this. My first two films, Pather Panchali and Aparajito, had to be slow because of their subject matter. I knew I was taking a risk. What I didnât know was how difficult it is to sustain a slow pace without seeming ponderous and boring. Provided the subject is interesting, a film can hold an audience in spite of slowness by means of (a) an extreme precision of cutting which ensures that shots are not held even for a split second beyond their expressive limits, and (b) an expressive soundtrack that helps to mitigate the slowness. A scene with its soundtrack turned off seems slower than it actually is because it withholds information, and is therefore less meaningful. Both Pather Panchali and Aparajito were rushed in the editing stage because of deadlines, and both had inadequate soundtracks. Faltering pace and long stretches of virtual silence affected the latter film more seriously because it was more episodic and less rich in human material than the first.

As for my other films, most of them are primarily about human relationships. To make characters credible and their interplay interesting needs footage.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Call Me by Your Name by André Aciman(20515)

Ready Player One by Cline Ernest(14675)

How to Be a Bawse: A Guide to Conquering Life by Lilly Singh(7486)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5783)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5178)

On Writing A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King(4943)

Audition by Ryu Murakami(4930)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4814)

Call me by your name by Andre Aciman(4682)

Gerald's Game by Stephen King(4654)

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child: The Journey by Harry Potter Theatrical Productions(4506)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(4401)

The Perils of Being Moderately Famous by Soha Ali Khan(4220)

Dynamic Alignment Through Imagery by Eric Franklin(4216)

Apollo 8 by Jeffrey Kluger(3707)

The Inner Game of Tennis by W. Timothy Gallwey(3687)

Seriously... I'm Kidding by Ellen DeGeneres(3633)

How to be Champion: My Autobiography by Sarah Millican(3593)

Darker by E L James(3516)